“So, why is this important?”, one might ask. While some buyers really don’t care what fiber a garment is made of, many do. Some can’t wear synthetics, some can’t wear certain natural fibers. For others, it’s a matter of preference. And, for both buyers and sellers, knowing the fiber can determine how to care for/clean/store the garment. This subject is so expansive and can be so complex, I don’t expect every seller to be a fabric expert! I don’t consider myself one, at that. But, since fiber-content labels are a relatively recent development in apparel manufacturing, all sellers need a basic understanding of fiber and weave, and how to recognize them. This information is important to buyers too, because knowing the fiber can help them get a sense of how the fabric will feel and drape (or not) on the body.

People often know weaves but don’t realize that several different fibers can be used to create the same weave. This seems to commonly occur with satin, taffeta, chiffon, jersey, velvet, gabardine, jacquard, seersucker, tweed, and a few others. Since this would be a book and not a blog if I addressed all of them, I’ll start with the first three:

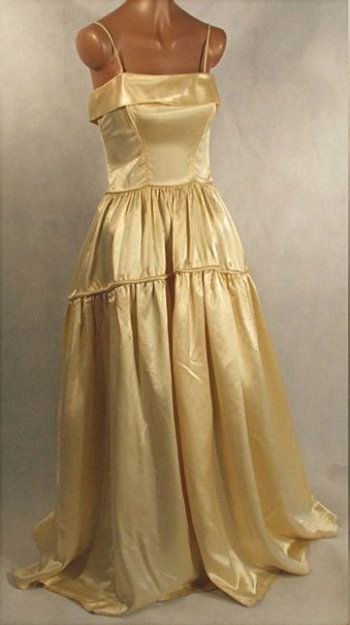

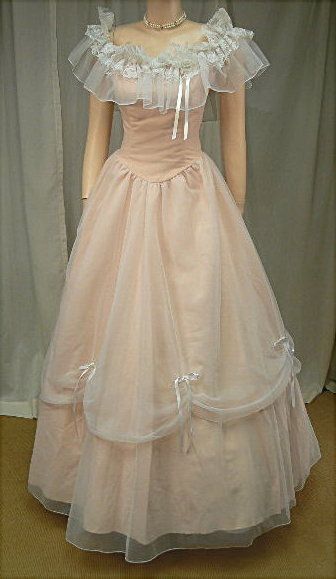

Satin: Most folks know satin, that shiny, smooth-textured, “slippery” fabric from which many evening and wedding gowns, nicer lingerie, and some linings are made. It can be made from silk, rayon, and polyester, and, sometimes, acetate. Cotton satin is called “sateen.” De-lustered, or matte, satin is often done in silk and called “peau de soie.” It has a very subtle luster and is delightful! You can see the difference in sheen in these two dresses, one a traditional rayon satin, the other a peau de soie:

Rayon satin Fred Perlberg gown from Alley Cats Vintage:

Pink peau de soie dress from Catseye Vintage:

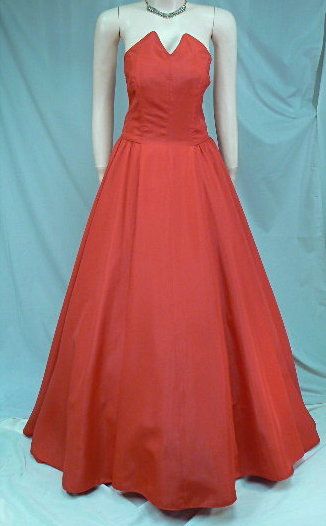

Taffeta: Also a smooth, finely woven fabric with a sheen to it, but is “crisp” and usually thinner than satin. It was very popular in the full-skirted party dresses of the 50s, often layered with tulle. Now commonly used in dress and coat linings. Though we usually see it in acetate or rayon, it used to be made mostly of silk. Nylon also can be woven into a taffeta finish—most notably the Barbizon “Tafredda” slips (when I got my first one, I was astounded that it was 100% nylon!).

Abbey Kent silk taffeta dress from Vintage Baubles:

Red rayon taffeta evening gown from Vintage Baubles Too:

Chiffon: That sheer, thin, and airy fabric seen in party dresses, wedding gowns, etc. Vintage double-chiffon peignoir sets have been popular for years. Chiffon is often used for billowy sleeves, ruffled trim, and bodice insets. When used for a full garment, it’s often lined in taffeta. It can be made from silk, nylon, polyester, and rayon.

Print silk-chiffon dress sold by Vintage Baubles:

Nylon chiffon gown sold by Vintage Baubles:

How to tell the difference? The best way is through handling as many different known fibers and weaves as you can. Note the content and weave of modern and vintage garments you already have--how they feel, how they drape, etc. Go to the fabric store, take a bolt of silk satin and one of polyester satin, and compare the feel. There is nothing like “hands-on” practice! Identifying fabrics will become much easier over time. But, no matter how well versed you are, sometimes you just can’t tell. I have three sewing books I use as reference; after sewing for 40 years and selling for 10, I still check them. Often. You should also learn how to do a burn test for fibers you can’t identify. This isn’t always possible, but it can be valuable when it is. Do a search for “fiber burn test,” and you’ll find charts, tips on methodology, etc. Bear in mind that any of the fabrics discussed today can consist of blends of fibers, and in that case, even a burn test may be inconclusive.

So, sometimes, if you’re a seller, you end up just not being sure. In that case, I generally state my best guess as to fiber. In online selling, where a buyer can’t handle an item, I think it’s critical to state, to the extent possible, the fiber and weave of a piece. I don’t know about you, but I wouldn’t spend hundreds of dollars to purchase a dress online without any idea of what fiber it is!

Be sure to keep an eye out for the next installment of "The Fabric Junkie"!

3 comments:

Wonderful Items!!!!

" I have three sewing books I use as reference; after sewing for 40 years and selling for 10, I still check them. Often."

So, may I ask, what are those three? Very curious, as I sell fabric and do not always know what it is.

Thank you.

Hi Katjoy, thanks for reading our blog! My first "go-to" resource when researching a fabric is my 1968 "McCall's Sewing Book." It's got a terrific chapter on fabric--fiber, weaves and how they are fashioned, finishes,and a great glossary of familiar fabrics, complete with many photos. Most of the time this book, along with my past experience, answers my "what fabric is it?" question. On occasion I'll back up that with my "Penguin Book of Sewing" and/or my Coates & Clark's "Sewing Book." Of course I use online fabric sites, but that McCall's book is the first place I go! I'm sure there are more thorough reference books available, but for what I need, My McCall's is sufficient. I've taken more to using burn tests as well these days.

Post a Comment